Antonio Manuel Rodríguez Ramos

Doctor en Derecho. Profesor Derecho Civil de la Universidad de Córdoba

Abstract: There are three questions regarding the Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba: ownership (public or private), management (public, private or shared) and use (civil, ecumenical or Catholic). Nobody questions its public nature nor its universal transcendence. This article is limited to the legal examination of the public ownership of the Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba as well as the nullity of its public registration by Catholic Church due to the unconstitutional nature of the laws which protect this act, the lack of a physical title of acquisition and the impossibility of acquiring it.

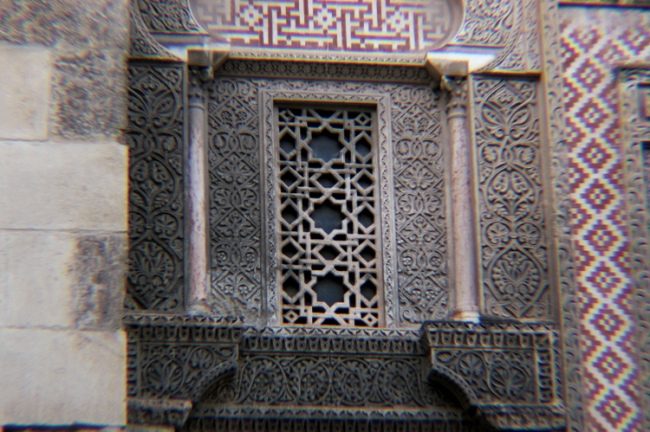

The popularly called Mezquita of Córdoba, (Mosque of Córdoba), also known as the Santísma Iglesia Catedral by the Catholic Church, isn’t one thing or the other: It is both or it is neither. It is either an ecumenical temple prepared for shared prayer, or a secular monument like Santa Sofia in Istanbul. In this way, the debate can be resolved over the function of this unique monument, which is the universal claim of Cordoba, catalogued and protected with public money as a Property of Cultural Interest (GCI) by the Ministry of Culture, declared a National Monument in 1882 and declared a World Cultural Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1984. We are speaking about a political decision that would be consistent with its historical, artistic and spiritual transcendence which would have been possible only a few years ago if it weren’t because it apparently no longer belongs to the people of Cordoba, nor to the people of Andalusia, nor to the people of Spain: It is the private property of the Catholic Church. Is this true? Was the acquisition legitimate? In my judgment, without a doubt the answer is no.

The 2nd of March, coinciding with the problem of the wooden beams in auction, the Catholic Church for the first time registered La Mezquita in the Property Registry as “Santa Iglesia Catedral de Córdoba”. In its name, of course. Nobody had done anything before in this respect. Not the Town Hall that occupied it de facto without paying the IBI (which is acceptable in this case being that it doesn’t belong to them) nor the public administrations that subsidize its renovations with everyone’s money. A simple law would have been enough to catalogue it as a titled, public property. Why wasn’t it done?

The Bishopric claimed as the 100% justified title for its appropriation the “takeover” (not of property) in 1236 A.D. when a band of ashes was drawn on the ground in the form of a cross with the letters of the Latin and Greek alphabets. The possession/occupation in time is not a valid way to acquire publically owned property. Not with the Aqueduct of Segovia, nor the Theater of Mérida, nor the Alhambra. Nevertheless, the Mezquita-Catedral of Córdoba was not inventoried as a property of the public domain. Why? Because of its obvious nature and because of misleading legislation. Until the alteration to article 54 of the Mortgage Regulation, implemented by Royal Decree in 1998, the temples set aside for Catholic worship were left out of the Registry and were considered “property of the public domain”. Undoubtedly, not all were left out, but this affirmation was as coherent in an IntegristaState (national-Catholic) as inadmissible in a secular State. Knowingly or not, that alteration didn’t address two “pre-constitutional” articles (which I will reference later) which equate the Catholic Church to an administration and which attribute to the Catholic Dioceses the functionality of public authenticating officer. This double and flagrant unconstitutionality turns the spirit of the law inside out like a sock: everything that was before public (because of the symbiosis of the Church-State) is now susceptible to private appropriation. Taking advantage of this oversight, which no one corrected after, the Catholic Church has registered for the first time thousands of properties, theirs or not, private or public, the most symbolic being the Mezquita Catedral de Córdoba. This is the text that appears in the Register of the Property attributing the title to the Town Hall and the exclusive use for “Catholic worship”.

“URBANA-SANTA IGLESIA CATEDRAL DE CORDOBA, located at number one Cardenal Herrero Street, Córdoba; consisting of a surface extention of 20,396 meters squared, with the same constructed surface area, according to the descriptive and graphic certification provided by the Territorial Management of the Property Register with the cooperation of the local Treasury Department, the 21st of February, 2006 which is included. Beautiful, seen from the entrance, to the right with Torrijos Street; to the left with Magistral González Francés Street; from behind with Corregidor Luis de la Cerda Street; from the front with Cardinal Herrero Street. Ancient Visigoth Basilica of San Vincente and mosque. The city reconquered by Ferdinand III The Holy, the monarch arranged for it to be dedicated to Holy Mary the Mother of God on the festival of the Apostles Saint Peter and Saint Paul in the year 1236 and for it to be consecrated the same day by the Bishop of Osma Don Juan Dominguez in the absence of the Archbishop of Toledo Don Rodrigo Jimenez de Rada, attended by the Bishops of Cuenca, Baeza, Plasencia and Coria. The ceremony of drawing the letters of the Greek and Latin alphabets with the crosier on a band of ashes extended on the pavement in the form of a diagonal cross was the liturgical and canonical expression of the seizure by the Church. The entire building was converted into a Christian temple, but it didn’t acquire it quality of a Cathedral until the election of the first Bishop, Don Lope de Fitero, shortly after the month of November 1238 and its Episcopal consecration one day during the first months of the following year. The Cathedral was declared a national monument in 1882 and World Heritage Monument in 1984. The building is dedicated to Catholic Worship.”

The Bishopric calls it “Santa Iglesia Catedral de Córdoba”. It commits a metonymy and calls the whole building by the name of one part of it. Precisely the least authentic and least known part. It is evident that not all of the Mezquita is a Cathedral, no matter how much the file of the registry proclaims it. It was curiously named only the “Mezquita” in the Registry in a comical and revealing thoughtless mistake. Among the proof that demonstrates this concept, perhaps the most convincing is the UNESCO declaration on November 2nd 1984 in Buenos Aires of “The Mosque of Córdoba” as a World Cultural Heritage Site.

However, this process of amputation from the collective memory by the Catholic Church (in the rregistry references, in the management of the monument and in its spiritual use), culminating in the legal, symbolic and spiritual appropriation of the Mezquita de Córdoba suffers from clumsy material and legal errors in the title as well as in the acquisition.

In short, the registration is only the proof of the existence of a right, not a manner of acquisition. Consequently, the existence of a physical title and antecedent is always necessary to justify the legal ownership of real estate, which must also be susceptible as private property. For the case of the Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba there is no physical title because “consecration” isn’t a manner of acquisition recognized in our Law; the property is neither susceptible as private property because of belonging to the public domain and having public ownership; and the laws which formally protect the registration are unconstitutional. Therefore the registration is legally null without any necessity for an explicit law of disentailment. Simply put, it would be enough if the articles 206 of the Mortgage Law and 304 of its Reglamento were declared unconstitutional either by the Tribunal Constitucional or by a Juez de Instancia regarding a supervening unconstitutionality. It would also be enough if there were administrative recognition of the public nature of the property. And in both cases, in order to make the return to civil ownership effective, neither expropriation nor paying an appraisal would be necessary because it was never the property of the Church. In the strictest sense, there wouldn’t be a return of ownership because it has always been public.

I will try to lay out these arguments superficially.

1.-Registration is absolutely not supposed to mean the acquisition of legal ownership of the property. The registration in the Register is only proof, convincing without a doubt, of the supposed existence of the right and, consequently, can be dismantled when it is demonstrated that the reality of the situation doesn’t corroborate what is legally said in the registration. Just because I register the moon in my name doesn’t mean that it’s mine.

Including a registration like this isn’t opposable by third parties until two years have passed (article 207 LH). Until then anyone could attack the validity of the alleged acquired ownership. Casually, the Ley de Patrimonio Histórico Andaluz is passed in 2007. And in an additional ruling exclusively dedicated to the Catholic Church, the Administración Andaluz renounced the rights of judgement and recovery regarding properties registered in the way. In just one year, the Catholic Church had secured in appearance the property papers over the Mezquita-Catedral that it didn’t have before and from that point onward it would be called in its pamphlets exclusively as the Santísima Iglesia Catedral de Córdoba. Considering one part of the building as being the entire structure and holding it all as its own.

2-The articles that permit the registration (206 Mortgage Law and 304 Reglamento Hipotecario) are by any reckoning unconstitutional. Until the reform to article 5.4 of the Reglamento Hipotecario, perpetrated by Royal Decree 1867/1998 on the 4th of September (BOE 29th of September 1998), temples dedicated to Catholic worship were excluded from access to the Registro de la Propriedad, in comparison with the public properties of an Integrist State of Francoist National Catholicism but completely inadmissible in a constitutionally “secular” State. Nevertheless, the reform didn’t address two “pre-constitutional” articles which equate the Catholic Church with and administration and attribute to Catholic Dioceses the functionality of public authenticating officer. Unconstitutional on two parts.

Article 206 of the Mortgage Law says: “The State, the Province, the Municipal and the Corporaciónes de Derecho Público or organized services that form part of it and those of the Catholic Church, when they lack a registered title of ownership, they will be able to register for a property title through the timely certification processed by the civil servant whose job is the administration of such issues, in which the title of acquisition or the manner in which the properties were acquired will be expressed.”

And article 304 Reglamento Hipotecario: “In the case that the civil servant in whose charge is the administration or custody of the properties doesn’t exercise the public authority nor has the ability to certify, the certification will be issued, as referred in the previous article, to the immediate hierarchical superior who is able to certify, taking note of all of the facts and official information that are indispensible. In regards to the properties of the Church, the certifications will be issued by the respective Dioceses.

Both precepts collide with article 16.3 of the Constitución Española (and article 1.3 Ley Organica de Liberdad Religiosa), that establishes that “no religion will be of a national character”. The Catholic Church cannot be considered in any way as a public administration, nor can any of its members be considered civil servants. The contrary contradicts the constitutional principle of the separation of church and state.

Both articles are affected by supervening unconstitutionality. This assumes that the Jueces y Tribunales should have them repealed and, consequently, null any actions protected by them. From its first ruling (STC 4/1981, February 2nd of 1981) the Tribunal Constitucional settled with clarity and conclusiveness that “peculiarity of the pre-constitutional laws consist in, for what interests us at the moment, that the Constitution is a superior law, hierarchical criteria, and posterior temporal criteria. And the concurrence of this double criteria gives rise-in part-to the supervening unconstitutionality and following invalidity of laws that are opposed to the Constitution and-in part-to the loss of their applicability towards future situations. In other words, their annulment”. And it adds that: “Thus in regards to the post-constitutional laws the Tribunal holds the exclusive right to judge their conformity with the Constitution, in relation to the pre-constitutional laws, the Jueces y Tribunales shouldn’t apply them if they understand that they have been annulled by the Constitution by being in direct opposition to it; or they can, in the case of doubt, submit the issue to the Tribunal Constitucional by way of the question of its unconstitutional nature”.

Assuming that a doubt exist, there also exists the doctrine of Tribunal Constitucional in relation to article 76.1 of the Texto Refundido of the Ley de Arrendamientos Urbanos of the 24th of December, 1994, which as with the cited articles, equates the Catholic Church with “The State, the Province, the Municipal and the Coporaciónes de Derecho Público” exempting it from the obligation to justify the need for occupying the properties that it had in lease. The STC 340/1993 of the 16th of November settled without fissure that religious ends cannot be equated to public ends, especially when it includes the paradox of considering the rei sacrae as public things and at the same time as private property of the Catholic Church. It assumes the violation of the principle of equality (article 14 CE) with other religions, without the judgment by the Tribunal Constitucional that there exists a competent, objective and reasonable justification

3.-The consecration isn’t a way of property acquisition. The article 609 of the Código Civil establishes the different ways in which legal ownership of available properties can be acquired. And among them, as is logical, “consecration” does not appear. If this were the case, the Sagrada Familia would have come under the possession of the VaticanState when it was blessed by the Pope.

4.-Public properties are not acquired by possession in time. The key question. The public writing and the Registro de la Propiedad speak of the “takeover”. If the property were available for private ownership, the Catholic Church could argue its acquisition by the so called “usucapion”. But this isn’t the case because the Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba belongs to the State. I’m not going to make reference to the perverse and inappropriate term “reconquista”. Even granting the ownership by conquest to the Castilian Monarch, the Mezquita-Catedral continues being civilly and publically owned.

When the ecclesiastic Bishopric wanted to destroy the central arches of the Mezquita in order to construct the Cathedral, the Municipal Bishopric was opposed and even threatened punishment of death to anyone who dared touch the arches. Thus it appears in the Actas Capitulares of 1520 and in a Real Provisión dated in Loja on the 14th of July of 1523, declaring the Chancillería that the Provisor of Córdoba made an effort in not granting the appeals that the Town Hall had put in the lawsuit ordering that excommunion be included as well. The royal sentence of Carlos V permitted construction, although after he may have regretted this in his visit in 1526: “I didn’t not what this was; I wouldn’t have allowed it to reach the old part, because you do what can be done in other places and you have undone what was singular in the world”.

And it wasn’t the first time the monarchy, that’s to say, the State, had to resolve an issue. In the Actas Capitulares of 1523, Town Hall of the 29th of April, before the demolition of part of the Mezquita by the Church, it is said that, “the way which this temple is built in unique in the world and a great amount of treasure was spent in its construction and the principal inconvenience is that the Royal chapel be incorporated in the main altar where the kings are buried”…And it is added that “another time the earlier dean and Town Hall

In both cases, the royal decisions (negative by Isabel and permissive by Carlos I) demonstrate that it wasn’t in the Bishop’s power to make decisions alone about the monument. It wasn’t his. The final dispute was resolved by Carlos I. The King. The central power. As a result, the issue concerns public property, a world cultural heritage, and not private property that could be mortgaged tomorrow. And if it is public, like the Alhambra, it cannot be acquired by its extended possession in time. Even more: it should be managed by a public trust, in the best of cases with the participation of the Church, but never as a monopoly nor as a majority and always with the accounts clear. Its restoration, conservation and its nocturnal adaptation have been paid for with public money. All of us citizens have paid for it, even though the Church receives all of the money made from charging entrance and we do not know how much it makes doing so.

The municipal never lost authority over the monument. It was the municipal alone who asked for it to be declared a World Cultural Heritage Site by UNESCO referring to it only as “The Mosque of Córdoba” with three paragraphs included in which it is only mentioned as such.

But unlike the times of opposition to the ecclesiastical chapter, the municipal has kept silent regarding the entrance tickets and signs which only say Cathedral; in the pamphlets they call the Mezquita “Islamic intervention in the Cathedral” (something like calling a reservoir “the intervention of a river in the dam”); and in the “nocturnal catechesis” which has become the sad audiovisual show, the very existence of the Islamic and Andalusian art in the Mezquita is denied. Even Islam itself. It isn’t free to that its arches are copied from the aqueduct of Segovia or that the Mihrab is inspired by the Basílica de San Juan Evangelista. It even goes as far as to say that “Fernando III saves the Cathedral from the Islamic destruction” and it ends with a “Gloria” that finishes off a concert of sacred C atholic music. All of this is more proof of the intent to destroy proof. Premeditated. And unsuccessful: Memory is stronger than stones. The people continue calling it the Mezquita because each person calls what is theirs however they want.

5.-The apparent risk of the “usucapión secumdum tabulas”. Córdoba lost its candidacy for European Cultural Capital and, if nobody does anything, it will also lose its Mezquita-Catedral in 2016. It has been made clear that the Church’s registration of it does not make it the Church’s. But its access to the registry allows it to wrongly think that it can be thought of as private property and, as a result, acquirable by usucapion. That’s to say, by the extended possession in time with the expected requisites of the law.

To this effect, the article 35 Ley hipotecaria considers the registration as proper title and assumes that the holder has been in possession of the property publicly, peacefully, uninterruptedly and in good faith during the term of the entry. In this way it would be enough to be in possession of the property for only 10 years in order to make it apparently theirs. Exactly in 2016. Let it be clear that it would only be in appearance, given the fact that not even in this way could it lose its imprescriptible condition of public ownership. Thanks to the historical opposition of the people of Córdoba to the Town Hall, the Mezquita was not converted into another Cathedral. That it was Carlos I who resolved that conflict to regret it later, demonstrates that it never belonged to the Church. For this reason, as a citizen of Córdoba, I demand the Andalusian or state Administration to recognize the public ownership of the Mezquita-Catedral in order to avoid it being acquired or mortgaged like any other private property. Because then our only hope would be limited to the utopian eviction of the Church for failure to pay.

Hello,

is there any possibility to sign a petition in favor of saving the status of the mezquita as universal, religions-relating symbol?

Petra